On any given day, third grade teacher Andrew Ardley sees several colleagues walk out of school with bruises, bite marks and blood on them.

The rise of violence in public schools has been getting out of control for years, he says, and it’s only getting worse.

“We’ve got teachers not making this a career for any more than five years now. They’re walking away,” Ardley says in an interview with our newsroom.

The Nova Scotia Teachers Union voted 98 per cent in favour of a strike mandate on Thursday. That means, ahead of conciliation meetings with the provincial government on Monday and Tuesday, the union now has the power to call a strike.

However, the union has to wait a certain period of time before going down that road.

The union says teachers face multiple issues, like poor working conditions, poor teacher retention, wages and rising amounts of violence in schools.

With 13 years left until he can retire, Ardley says it’s getting harder and harder to choose to stay, for many of these reasons, the violence included.

The education system hasn’t always been like this, he says. It’s changed dramatically in the last 10 years, but he says especially in the last five.

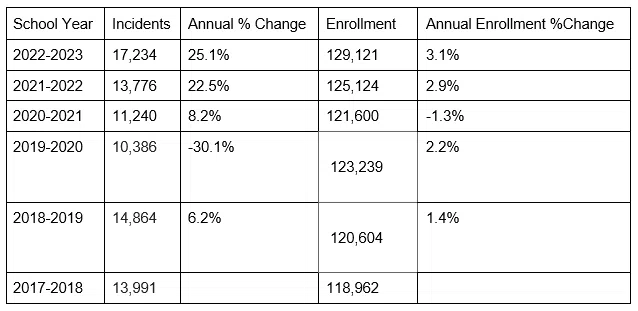

Increase in violent incidents since 2018

In the 2017-18 school year, there were 13,991 incidents of violence reported by schools in Nova Scotia, according to statistics acquired by a right to information request recently filed by the Nova Scotia NDP.

However, that number increases to 17,234 incidents of violence reported for the 2022-23 school year.

The number of violent incidents in schools has increased by 23.1 per cent since 2017, but the number of students only went up 8.5 per cent. Student enrollment in 2017-18 was 118,962, and in 2022-23 it was 129,121.

These statistics, provided by the Nova Scotia NDP, are based on data obtained through right to information requests. It shows the amount of violent incidents that happened in Nova Scotia schools since the 2017-18 school year. It also shows the amount of students enrolled in schools during that time.

The Provincial School Code of Conduct Policy defines physical violence as: “using force, gesturing, or inciting others to use force to injure a member of the school community.”

Ardley believes that students may be more violent for several reasons. Teachers have to compete with a “three-minute attention span because of how the digital media world has changed,” he says. If teachers don’t grab their attention fast enough, then they could get violent.

It can also be how people deal with the violent incidents. It’s not necessarily the responsibility of teachers, he says. It’s a higher up issue, meaning part of the solution comes from the government.

“I have to abide by the rules of my administration, who are abiding by the rules of their supervisors, and so on,” he says.

The union has said a lack of resources, like proper counselors and staff to work with children, is one of the causes of poor working conditions for teachers.

More violent incidents from elementary to sixth grade

Most of the violence comes from children in elementary schools.

According to the documents, about 75 per cent of violent incidents reported in 2021-22 were from students up to sixth grade. About 77 per cent of violent incidents reported were from that age group the next year, 2022-23.

“We’re seeing some behaviours at lower elementary we haven’t seen before,” says Scott Armstrong, chair of the Public School Administrators Association of Nova Scotia, which represents principals, vice-principals and school administrators.

“This is not just Nova Scotia. This is something that’s a trend in education,” says Armstrong.

Armstrong says that trend coincides with the COVID-1 pandemic. Part of that could be, while students in particularly lower grades were home, he says their social skills didn’t develop in the same way they would have while at school.

It’s something that needs to be addressed, Armstrong says.

“It’s something that I know the government, the union and our organization, have struck a committee that is working on some of these issues about violence and safe and inclusive schools.”

Armstrong hopes the committee, working with the education department in Nova Scotia, will “produce some actions” to reduce violence in schools.